Sliding Glass Panels in Art Deco and Streamline Moderne Design

While the Art Deco era (1920s-early 1940s) was a period of new material development, the style also embraced some really old materials as well, putting its own unique spin on them. One example of this was

Lighted Table, Opaline Glass, Wrought Iron Base, Atributed to Louis

Katona, c. 1925, 1st Dibs

the use of veneered wood (rebranded as plywood) in the 1920s and 30s. Another was the use of iron, something which was not quite as dramatically changed, just formed in ways that fit the new modern style.

Wrought Iron an alloy with very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) which is easier to work than iron with a high carbon content. It is made by heating high carbon iron in an open furnace or hearth causing some of the carbon to be removed when it bonds with oxygen. This increases the melting point and makes it easier to work (more malleable).

It's first production dates to about 200 BC in China and around the 12th century AD in Western Europe. As with many materials, the process of creating wrought iron was improved over time, finding better ways to heat higher carbon iron. The production process was still being refined during the Art Deco era. Engineer James Aston developed a process to produce wrought iron quickly and economically in 1925. Yet this was one of the last major changes to the process of making wrought iron as it had been declining in use for decades by then.

Up until the mid-late 19th century, wrought iron had been in structural applications. However, as steel production techniques improved and the price came down, it had largely replaced wrought iron in this capacity by 1890. Techniques and and designs used by French metal smiths caused wrought iron to transition from a structural material to a decorative one in the 20th century. By the 1910s, fine Art Nouveau style home decor items began being produced, including racks, etageres, table bases, desks, gates, beds, candle holders, curtain rods, bars, and bar stools. ("Wrought Iron", Wikipedia, gathered 6-10-25)

Much of the change

Art Nouveau Plant Stand, Emile Robert, c. 1900, Robert Zehil Gallery

in perception of wrought iron from a structural material to a decorative one can be traced back to Émile Robert, a French Master Blacksmith sometimes referred to as 'the father of modern French ironwork'. Working in the 1910s, Robert's designs were primarily Art Nouveau style. His impact on Art Deco is not to be diminished, however. The Architectural Forum magazine declared in January of 1929,

The present golden era in the art of metal working in France can be traced to the influence exerted even then by Emile Robert. ...The men who are now turning out the simplified and harmonious pieces so deservedly admired are pupils of Robert or are artists who have followed the trail blazed by him. It was Robert who first showed that wrought iron decoration was possible with out constant recourse to use of the acanthus leaf, and while he came too early to be identified with the present art moderne formula now referred to as Art Deco] , his work has in it the elements of logic and clarity and modernism that characterize the decorative art of the moment. (Francklyn Paris, "The Rejuvenescence of Wrought Iron", The Architectural Forum, Jan. 1929, p. 90)

By the 1920s wrought iron items in Art Deco style began to be made which removed some of the sinuous curves found in Nouveau designs utilizing instead more geometric designs. "...People loved the look of metal in their homes and wanted to incorporate it into their décor. Wrought iron furniture was made by hand and was very expensive. It was a sign of wealth and status to have wrought iron furniture in your home." ("1930 Art Deco Metal Wrought Iron Furniture Designers", the furniture rooms website, gathered 6-11-25)

While the style of many of these works was Art Deco, it still had the underpinnings of Arts & Craft, relying on the skill of the metal craftsman. (This is true of other Art Deco designs in the 1920s when wealthy clients hired Art Deco designers to create unique home designs for them.) Some of the Art Deco era metal artisans in France began to push production in the direction of mass production, employing newly developed tools and metalworking techniques. In addition, the change in style from Nouveau to Deco simplified designs facilitating somewhat faster production of wrought iron products. The bigger Art Deco era shops had hundreds of workers producing wrought iron and other metalwork products.

Some of Roberts' students went on to become fairly well-known for their Art Deco wrought iron designs.

Raymond Subes was one of Roberts' pupils who started working for him in 1916, learning the techniques required to create modern ironwork. He switched to one of Robert's Parisian contracting companies in 1919, becoming the head of their design department and the wrought iron workshop in the 1920s. He created furniture and architectural designs in the 1920s and 30s."His work predominantly featured patinated, chromed, or gilded wrought iron, polished steel, bronze, and repoussé copper. He incorporated alabaster, Levantine marble, frosted glass, and embroidered silk shades... Subes's work was more austere than that of his contemporaries. He used welding but preferred to leave the impression of the hammer on his metal." ("Raymond Subes (1893 – 1970), French Metalsmith", encyclopedia.design website, gathered 6-11-25)

Examples of Raymond Subes Wrought Iron Work, From left: Table, Wrought Iron Base with Marble Top, Raymond Subes, c. 1935, Macklowe Gallery; Chairs, Wrought Iron and Fabric, 1924, Ebay; Console Table, Wrought Iron and Marble, Raymond Subes, 1925, Pinterest; Wall Lamp (Sconce), Wrought Iron and Pate de Verre, Raymond Subes, c. 1925, Invaluable; Fire Grate with Deer, Wrought Iron, c. 1925, Chairish

Jean Prouvé was first apprenticed to Robert around 1917 and then to the Parisian metal workshop of Hungarian-born Aldabert-Georges Szabo. While Prouvé was apprenticed to him, Szabo produced items in a historic style rather than Art Nouveau until the first World War ended, switching to Art Deco styles after that. Prouvé began taking personal commissions in 1918. He left Szabo in 1921, likely focusing on his commissions for the next two years. He opened his own workshop in Nancy in 1923, producing wrought iron lamps, sconces, chandeliers, ramps, hand rails and gates. His wrought iron work seems to have been primarily focused on architectural pieces, being commissioned to produce wrought iron Art Deco designs for local architects during ensuing 16 years. He collaborated with several Modernist-inspired designers such as Robert Mallet-Stevens, Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret. His focus shifted from Arts and Crafts production of wrought iron to steel items which could be better mass produced with the establishment of his second business in 1931. Many of his metal furniture pieces were steel.

Examples of Jean Prouvé Wrought Iron Work, From left: Front Door Wings, Jean Prouvé, 1930, Kreutze; Staircase Railing, Hoel de l'Ermitage, Vittel, France, 1928, Jean Prouve website; Entrance Door, Villa Reifenberg, Jean Prouvé for Robert Mallet-Stevens, 1928, X

Not all those creating Art Deco wrought iron products were students of Robert, although they certainly owed much to the way he

Pelican Bookends, Cast and Wrought Iron, Edgar Brandt, 1924, Deconamic

shifted the focus of the material from structural to ornamental designs. Let's consider some of the others working in wrought iron and producing Art Deco designs.

Perrhaps the best known artist working with wrought iron during this time was Frenchman Edgar Brandt. He had begun designing furniture during the height of the Art Nouveau period, employing a variety of materials including iron, steel, bronze and wood. In 1919, following the end of the war, Brandt opened his own workshop, La Maison d'un Ferronnier. He regularly displayed his designs at the Salon d'Automne and Salon des Artistes Decorateurs in Paris and had an important presence at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. In Art Deco fashion, Brandt stylized his designs in the 1920s, using abstractions and an irregular spiraling technique to create flowers and plants. He referenced other cultures including ancient Egypt and Greece, Japan and Africa. When Art Deco designs became more streamlined in the late 20s and 30s, he did so as well. "In his later work, one can see how Brandt's work shows a progression towards abstraction as a result of trying to reflect the new Modernist aesthetic." ("Edgar Brandt", Wikipedia, gathered 6-10-25)

Brandt was at the forefront of moving metalwork towards mass production. At its height, his company employed more the 3000 specialized workers. He embraced new technologies which facilitated faster production, mastering the use of the oxyacetylene torch shortly after its creation in the 1903 and adopting new forging methods.

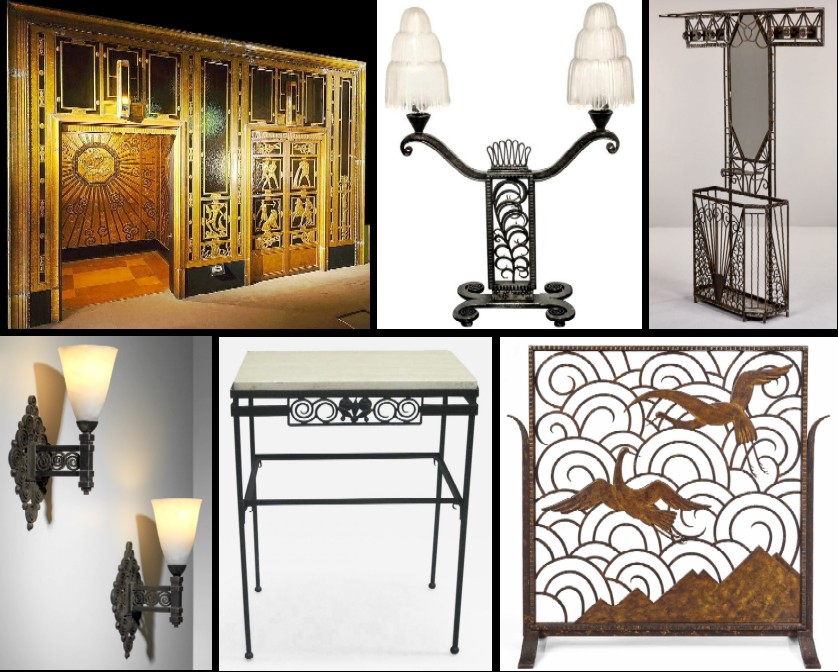

Examples of Edgar Brandt Wrought Iron Work, From top left: Elevators, Selfridges of London, Gilded Iron, Zodiac Signs and Chinoiserie, 1928; Table Lamp, Wrought Iron with Waterfall Sabino Shades, 1930s, Lampem, Hall Tree, Wrought Iron and Mirror, 1930s, Judy Frankel Antiques; Wall Sconces, Wrought Iron with Alabaster Shades, 1930s, Danke; Small Table, Wrought Iron with Stone Top, Incollect; Firescreen, Patinated and Gilt Wrought Iron, c. 1930, Lot Search

Paul Kiss created handcrafted wrought iron items for both residential and commercial use in the 20s and 30s. Born in Hungary, he moved to Paris in 1907 where he worked with Brandt and Subes. He created Art Deco furniture, lamps and mirrors which featured geometric designs as well as stylized people, plans and animals. Like his peers, Kiss created items for architectural use as well as monuments. In 1924, he won silver medal a the Salon des Artistes Francais for his war memorial in Levallois-Perret. During the 1920s, Kiss mentored French designer Paul Fehér who went on to join craftsman Martin Rose of Rose Iron Works in the United States.

Examples of Paul Kiss Wrought Iron Work, From left: Hall Stand, Bronze Patinated, c. 1930, Potamck Company; Wrought Iron, Console Table and Mirror, Gray Marble Top and Mirror, c. 1925, Invaluable; Floor Lamp, Wrought Iron with Alabater Shade, c. 1925, Christie's; Pedastal, Wrought Iron and Marble, c. 1925, Art Insitute of Chicago

Martin Rose started Rose Iron Works in 1904 in

Screen, Paul Feher for Rose Iron Works,

1930., Cleveland Historical

Cleveland. Like many of the French immigrants who set up shop there, he began producing iron work was used on buildings erected there as well as gates for houses. Rose visited Europe in 1926 where he was exposed to Art Deco metal designs. His son Melvin Rose explains, He brought the style back because he "saw in deco... a possibility of bringing a new, fresh look at design in our work to Cleveland." (Melvin Rose, "Art Deco and the Great Depression", Audio File, Cleveland Regional Oral History Collection, Cleveland Historical website, gathered 6-12-25) Even after the market crash of 1929, Rose Iron Works survived. " During the 1930s, the Rose Iron Works produced some of the most notable Art Deco ironwork in the nation, including styling recognized internationally for their uniquely American characteristics." ("Rose Iron Works", Cleveland Historical website, gathered 6-12-25)

Another American metal artist active

Screen, Samuel Yellin, c. 1930,

Minneapolist Institute of Art

during the Art Deco era who worked with wrought iron was Russian (now Ukrane) born Samuel Yellin who emigrated to Philadelphia in 1906 where he founded Yellin Metalworkers studio. Like other metal craftsmen of the period, he started out using traditional techniques, declaring, ""I am a staunch advocate of tradition in the matter of design. I think that we should follow the lead of the past masters and seek our inspiration from their wonderful work. They saw the poetry and rhythm of iron." ("Samuel Yellin, an Artisan in Iron", Vicaya Museum and Garden website, gathered 5-12-25) Yet his designs followed the styles of the times, including Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Modernism. The Minneapolis Institute of Art explains, "Through his European training, Yellin possessed an understanding of historical styles and employed them for clients, but his most memorable designs are from his Arts and Crafts and later modernist work." ("Screen, c. 1930, Samuel Yellin", Minneapolis Institute of Arts website, gathered 6-11-25) Nor does he appear to have been opposed to new developments in the metal working trade. By the 1930s, Yellin's Philadelphia shop had 60 forges for over 200 workers.

From all these examples, it will hopefully be seen that wrought iron products saw advances in design and benefitted from new tools during the Art Deco period, even if this didn't occur as much in material itself. While the 1920s and 30s were a period of improved materials, this shows that they were also a period improved design and production.

Console Table, Wrought Iron Base with Pink Marble Top, French, Soubrier

Sources Not Cited Above:

"Cast Iron", Wikipedia, gathered 6-10-25

"What is the history of ornamental ironwork?", Simen Metal website, gathered 6-11-25

Jennifer Yanyuk, "The Fascinating Journey of Wrought Iron: Tracing its Roots and Evolution", Black Badge Doors", gathered 6-11-25

"Adalbert-Georges Szabo", RSA Antiquitäten Wiesbaden website, gathered 6-11-25

"Jean Prouvé", Wikipedia, gathered 6-12-25

"The life of a designer", Jean Prouvé website, gathered 6-12-25

"Edgar Brandt", 1st Dibs website, gathered 6-11-25

"Edgar Brandt, (1880 - 1960)", Calderwood Gallery website, gathered 6-10-25

"Edgar Brandt - Life and Work", Galerie Claude website, gathered 6-10-25

"Paul Kiss" 1st Dibs, gathered 6-11-25

"Paul Kiss and Daum wrought iron and bronze lamp", 1930.fr website, gathered 6-11-25

"Samuel Yellin: Restoring Historic Ironworks", Vanderbilt Museum website, gathered 6-11-25

Christina Alphonso, "Samuel Yellin and the 'Poetry and Rhythm of Iron'", Met Museum website, gathered 6-11-25

Emma Yanoshik-Wing, James Calder, & Mark Tebeau, "Rose Iron Works: The Nation's Oldest Decorative Metalwork Company", Cleveland Historical website, gathered 6-11-25

Original Facebook Group Posting